The Russian Offensive of the summer of 1916 dealt a significant blow to the Austro-Hungarian Army, resulting in approximately 750,000 casualties. The primary tactical repercussion of this defeat manifested as a considerable breach in the defensive line, rendering its closure beyond the independent capacity of Austria-Hungary. The resolution necessitated a substantial influx of German assistance and troops. However, the German forces were preoccupied with engagements on other fronts, and the support they could extend proved insufficient. Consequently, this predicament compelled Turkish troops to venture into remote regions of Hungary, marking the first instance of such an occurrence since the 17th century.

The Russian Offensive of the summer of 1916 dealt a significant blow to the Austro-Hungarian Army, resulting in approximately 750,000 casualties. The primary tactical repercussion of this defeat manifested as a considerable breach in the defensive line, rendering its closure beyond the independent capacity of Austria-Hungary. The resolution necessitated a substantial influx of German assistance and troops. However, the German forces were preoccupied with engagements on other fronts, and the support they could extend proved insufficient. Consequently, this predicament compelled Turkish troops to venture into remote regions of Hungary, marking the first instance of such an occurrence since the 17th century.

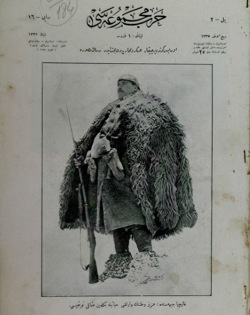

Following the culmination of the Gallipoli campaign, Mustafa Kemal's renowned 19th Infantry Division was relocated northwards to Keşan and Şarköy. In January 1916, it amalgamated with the 20th Infantry Division to establish the new XV Army Corps. On 10 July 1916, an edict from the Ottoman High Command directed the corps to be dispatched to Galicia, prompting the corps headquarters to determine the earliest feasible departure date.

Following the culmination of the Gallipoli campaign, Mustafa Kemal's renowned 19th Infantry Division was relocated northwards to Keşan and Şarköy. In January 1916, it amalgamated with the 20th Infantry Division to establish the new XV Army Corps. On 10 July 1916, an edict from the Ottoman High Command directed the corps to be dispatched to Galicia, prompting the corps headquarters to determine the earliest feasible departure date.

This undertaking presented considerable challenges. More than 30,000 men were tasked with traversing four distinct nations to reach an unfamiliar destination. Compounding the difficulty, their preparations were incomplete. A vanguard consisting of 13 officers and 34 troops commenced their journey by train on the day following the issuance of departure orders. According to the stipulated departure plan, the initial units were scheduled to arrive in Uzunköprü on 22 July 1916, with the final units departing on 11 August. Notably, only the infantry units of the 20th Division were to embark on the train in Alpullu, while all other units were designated to assemble in Uzunköprü.

Enver Pasha, displaying a sense of urgency, sought to expedite the troops' arrival at the front. Consequently, he directed the departure of two trains from Uzunköprü station daily until 29 July, with an additional train departing from Alpullu each day after 20 July. The corps headquarters, commanded by Colonel Yakup Şevki Bey, commenced their journey from Uzunköprü to various destinations in Hungary.

On 21 July, the 57th Regiment of the 19th Division, accompanied by an artillery battalion, commenced its departure, followed by the 20th Division on 22 July, and the remaining units of the 19th Division two days thereafter. The initial components of the corps arrived in Hungary on 5 August, and the complete corps deployment spanned a total of 22 days. The seamless execution of this movement was primarily attributable to the practice of trains, originally transporting ammunition from Germany to Turkey, routinely returning to Europe with empty wagons. The utilisation of these trains proved instrumental in facilitating the overall movement.

Upon his arrival, Colonel Yakup Şevki received information that the XV Army Corps had been assigned to Army South under the command of Lieutenant General Graf von Bothmer. The corps was tasked with overseeing a 28-kilometre stretch along the west bank of the Zlotalipa River. Flanking the corps' front were the 55th Infantry Division and the Bavarian 1st Reserve Division, both German divisions. Positioned opposite were elements of the Russian 47th and 113th Divisions, along with the 3rd Turkistan Division.

The first ever inspection of the frontline was conducted by Lieutenant Colonel Mehmet Şefik, commanding officer of the 19th Division, who traversed the line by car under moonlight on the night of 12/13 August. During this survey, he encountered engineering units and Austrian infantry elements, with distant sounds of artillery fire perceptible.

Archduke Karl of Austria paid a visit to Colonel Yakup Şevki and his staff on 20 August at the Hodorov station. Subsequently, General Bothmer visited the Turkish headquarters the following day, expressing his appreciation for the "privilege of commanding the valiant forces of Gallipoli, together with German, Austrian and Hungarian troops.”

On 22 August, Colonel Yakup Şevki disseminated a memorandum declaring that Turkish forces had assumed their designated positions and were poised for engagement. An aerial reconnaissance report from the neighbouring Hofmann Corps on the subsequent day revealed preparatory activities by Russian forces indicative of an impending assault.

First Contact with the Russians

The Russian offensive was initiated on 2 September, with the most intense initial combat occurring to the north of the Turkish corps, where the German 55th Division confronted a superior Russian force supported by intense artillery fire along a front that spanned a mere four kilometers. By midday, numerous Turkish regiments were actively engaged in battle. The 77th Regiment, being the first to make contact with the enemy, successfully repelled the Russian infantry that had crossed the Zlotolipa River. Simultaneously, the reserve battalion of the 19th Division received orders to move northward and provide support to the German division.

Despite these efforts, the Russians gained the upper hand. On 3 September, the Hofmann Corps executed a counterattack; however, it achieved no more than a deceleration of the opposing forces. During the night of 4/5 September, General Hofmann initiated a renewed assault, this time with a request for artillery support from the Turkish forces. Owing to the resolute defence of the Turkish battalion in the southern sector, which impeded the Russian advance, this offensive proved successful. Consequently, the Russians were compelled to retreat from their positions, marking their failure to breach the northern sector of the Turkish-German front line.

Following a triumphant offensive, the Turkish 20th Division discerned explosions emanating from the southern sector. The tumultuous sounds were attributed to an onslaught of heavy artillery fire, signalling a Russian offensive against the Gerok Group spanning a front line extending 25 kilometres. On the night of 5 September, confrontations along this front line intensified markedly. Despite successfully dislodging the Bavarian 1st Reserve Division from their entrenched positions earlier in the day, the Russian forces were compelled to retract subsequent to a resolute counterattack mounted by the Germans. Conversely, the Austrian units found themselves in precipitous retreat, rendering it unfeasible to impede the advancing Russian forces in this sector.

This development proved disconcerting for General Bothmer, as the southern progression of Russian forces indicated an imminent encirclement of the Gerok Group and the Turkish corps by the adversary. The constraints of time and resources precluded any effective resistance against the advancing Russian troops. Consequently, a strategic decision was made to order a retreat at 8:00 pm on 5 September. In accordance with this revised plan, the Gerok Group and the Turkish corps were instructed to effect a withdrawal spanning 20-30 kilometres, positioning themselves along a newly designated defensive line.

The Retreat

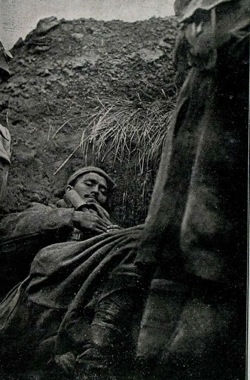

The directive to initiate a withdrawal was conveyed to the Turkish command amidst a state of confusion. Having had minimal engagement with the enemy, elucidating the rationale behind this retreat posed a formidable challenge. The soldiers, having sacrificed comrades in Gallipoli for mere metres of terrain, were now compelled to relinquish a substantial expanse of 20 kilometres. Not only were they averse to this proposition, but they also lacked the practical experience requisite for executing a retreat.

Given the potential disastrous consequences should the enemy become cognizant of the retreat, the evacuation had to be executed with utmost secrecy. The devised strategy involved designating eight battalions, constituting a third of the total 24 battalions across the 19th and 20th Divisions, to serve as a rear guard along the entrenchments on the western bank of the Zlotalipa River. Subsequently, these battalions would traverse the forest to reach the newly established defensive line, followed by the remaining battalions. The plan was set into motion at midnight, and the rear guards experienced an uneventful night, as the Russian forces remained dormant in their slumber.

On the mist-laden morning of 6 September, the Russians initiated a formidable assault on the entrenched positions. Turkish battalions endeavoured to retaliate, yet Russian commanders promptly discerned a reduction of two-thirds in the number of artillery units firing upon them compared to the preceding day. Concurrently, officers overseeing the rear guards of the Turkish forces found themselves confronted with a challenging dilemma. Their numerical strength proved inadequate to maintain the defensive line, yet a strategic withdrawal posed the risk of imperiling the two divisions due to insufficient time for preparation.

Lieutenant Colonel Bahattin Bey, commanding officer of the 61st Regiment and overseeing the units of the 20th Division in the rear guard, resolved to issue a partial retreat. Within his regiment, the 2nd Battalion stood ready, and he opted to retain solely the 5th Company while directing the remaining elements to withdraw. The Russians promptly discerned this tactical maneuver and directed their assault specifically towards this solitary company, resulting in substantial casualties for the Turkish forces.

These engagements demonstrated that a frontline spanning 16 kilometres proved excessively broad for a singular corps. In response to a plea from the corps commander, Colonel Yakup Şevki, the German command yielded a hill and its surrounding fields, within the purview of the 20th Division, to the Bavarian 1st Reserve Division. This reallocation served to contract the Turkish line. A period of tranquility ensued in Galicia during the subsequent days. Turkish and German forces dedicated efforts to fortifying their positions and remedying gaps, while Russian counterparts readied themselves for an assault in the Lipicadolna region to the south—a pivotal juncture linking the Turkish line with the Bavarian division.

The 61st Regiment experienced a forced withdrawal, rendering the situation highly precarious due to the depletion of tactical reserves after weeks of intense combat. At approximately 3:00 pm on the same day, the German 65th Brigade received orders to initiate a collaborative counter-attack, involving two battalions from the Turkish 20th Division. This marked the inaugural instance of joint military operations between German and Turkish forces. Despite significant challenges in coordination, notably the language barrier, the counter-attack proved highly successful, compelling the Russians to retreat to their initial positions. This event unfolded on 17 September. Subsequently, on the same date, Russian forces attempted another assault, only to be repelled by a determined Turkish bayonet charge.

Throughout the engagements on 16/17 September, the Turkish XV Corps incurred substantial losses, with 95 officers and 7,000 men falling in battle. Estimates of Russian casualties range between 15,000 and 20,000. The front remained stabilized for the remainder of September, with both factions executing localized and minor counter-attacks. In preparation for potential Russian offensives, the Germans allocated one infantry regiment, one cavalry regiment, and several artillery batteries to serve as reserves for the XV Army Corps. Reflecting on the events of this period, a Turkish soldier named İbrahim Efendi (Arıkan) chronicled in his memoirs that, despite the incurred losses, the solidarity between Turkish and German soldiers was notably profound.

On 30 September, hostilities ensued when the Russian 3rd Caucasian Corps launched an assault on the Turkish defensive line. Throughout the day, Turkish positions underwent multiple changes, yet ultimately, the Russians retreated without any territorial gains. The toll on Turkish forces for the day amounted to 45 officers and 5,000 men. Subsequently, on 5 and 6 October, the Russians initiated a renewed offensive, deploying 13 regiments. They successfully captured a hill, subsequently named Cevatbey Hill in honour of a fallen officer, situated in the southern sector of the Turkish defensive line, with the support of two regiments. However, after a protracted and intense engagement, four Turkish battalions reclaimed control of the hill. As per the corps command's report, this victory came at a cost of 15 officers and 3,000 men in casualties. Russian casualties were estimated at 12,000.

In reference to the battles of this period, Turkish officer Lieutenant Mehmet Şevki Bey documented in his diary that the Turkish forces had become accustomed to the style of warfare in Galicia. Possessing a clear understanding of the necessary tactics, they adeptly repelled the Russian attacks:

"On days of Russian attacks, intensive artillery fire lasting for more than 24 hours were opened on our front lines, which were loosely occupied by us. When firing began, we were evacuating those lines and moving gradually back all the way to the fourth lines. Eventually, the naïve Russian infantry would attack, only to face our hefty fire of destruction. Being exposed to this fire on an open field, these Mujiks were losing at least 80 percent of their men, however they could still outnumber us with their remaining 20 percent. They would continue to advance and come face to face with our infantry. A brief fist-to-fist fighting inside the forest and then a bomb and bayonet charge from our boys. A continuous chanting of 'Allah, Allah.' The Russians would retreat to where they have come from, we chase them and eventually we return to our own lines as well. The following Russian attacks would always follow the same routine and they always had to stop before our positions.” (Mehmet Şevki Bey)

Winter Sleep

On 8 October, Colonel Yakup Şevki, the Corps commander, attained the rank of brigadier general. The week subsequent to the intense battles of 5/6 September afforded the Turkish forces a commendable opportunity to recuperate and reorganize. Subsequently, there were minor Russian incursions to gain territory, but these were promptly repelled. Simultaneously, General Bothmer reduced the extent of the XV Corps sector by 10 kilometres, deploying the German 36th Infantry Division in the southern sector previously held by the Turkish 20th Division. This alteration presented a much-needed respite and rehabilitation opportunity for the Turkish troops.

On 10 November, Yakup Şevki Pasha returned to Turkey to assume command of the 14th Army Corps, with Brigadier General Cevat Pasha appointed as his successor.

The months of November and December 1916 transpired without significant engagements with the Russians. Winter conditions prevailed, prompting both sides to fortify their positions and equip their troops with winter uniforms.

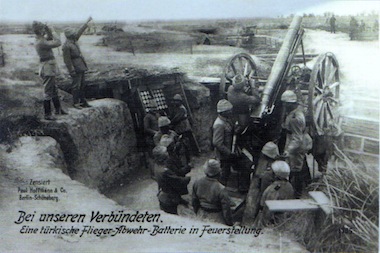

In early 1917, the manpower shortages within the XV Army Corps were ameliorated by the infusion of fresh troops from Turkey. Consequently, the strength of the XV Army Corps increased to 27,031 men, complemented by an additional 5,668 men undergoing training in regimental depots. The corps underwent a substantial reinforcement with the integration of new units, thereby augmenting its overall combat efficiency. These additions comprised artillery batteries, intelligence and labour detachments, an aircraft company, a balloon detachment, a field bakery company, transportation units, and a veterinary hospital. Turkish officers actively participated in training programmes.

The year 1917 started with a significant event, namely, the visit to the Turkish troops in Galicia by Crown Princes Abdurrahim and Osman on 4 January. This visit served as a considerable morale booster for the troops. Subsequently, on the following day, Kaiser Wilhelm conveyed an encouraging message, further uplifting the spirits of the military personnel. On 22 January, successful Turkish commanders and troops were honoured with the German Iron Cross, signifying their commendable achievements. Notably, on 4 February, Brigadier General Cevat Pasha paid a visit to Kaiser Wilhelm himself.

On 28 January, 17 and 25 February, Russian forces endeavored to seize Chikilani Hill situated in the northern sector of the Turkish theatre. These attempts proved unsuccessful, resulting in repulsion and considerable losses for the Russians. Several offensives conducted in March and April similarly yielded no tangible results, only inflicting heavy casualties upon the Russian forces.

A confidential directive from the Ottoman High Command reached Galicia on 10 April, outlining plans to redeploy the XV Army Corps to another front. The Germans expressed a favourable disposition towards this proposal. However, a definitive decision had not been reached, and this information was exclusively divulged to high-ranking officers. A few days later, two Russian soldiers, brandishing a white flag, approached the Turkish trenches. Initially indicative of a desire to cease hostilities, this amicable gesture was short-lived when the Russians took two German soldiers hostage.

Anticipating a forthcoming offensive, the Russians bolstered their forces with reinforcements from Siberian and Finnish troops. Premier Kerenski of Russia, accompanied by General Brusilov, visited the front, underscoring the significance of the impending military action. In May, a decisive order was issued for the XV Army Corps to return to Turkey. The 19th Division was directed to withdraw expeditiously, whereas the 20th Division was mandated to remain in Galicia for an extended period. Subsequently, between 11 June and 7 July 1917, the 19th Division completed its full relocation back to Turkey.

Russia’s Last Hope

A major Russian attack began on 29 June. Employing their newly acquired 205mm railway artillery guns and 155mm howitzers, the Turkish 20th Division, along with German units positioned on its flanks, exerted utmost effort in countering the relentless barrage of heavy artillery fire and the numerically superior Russian infantry. However, by 1 July, Turkish troops found themselves subjected to a gas attack orchestrated by Russian artillery shelling.

"We realized that the bullets were falling at the same spot, but they were not exploding, rather making only a little noise. We saw that a greenish yellow gas layer was slowly rising and widening. A chlorine cloud, just like the one that Mehmetçik had seen in Berlin, was surrounding us!.. The number of the bullets falling increased rapidly and soon we could see gas clouds rising not only to our left, but to our right, to our front and to our back, basically everywhere." (Mehmet Şevki Bey in his diary)

This chemical assault failed to yield any advantageous results for the Russian offensive. The untenable predicament faced by Russian troops culminated in their repulsion by the resolute Turkish forces, who, through three days of intense combat and valiant bayonet charges, successfully thwarted the aggressors. Remarkably, the Russian retreat transpired even prior to the arrival of the 250th German Regiment, dispatched as reinforcement for the beleaguered Turkish 20th Division.

Now it was time for the Turks to strike back. On 12 July, the Turkish offensive began with artillery fire from all positions. İbrahim Efendi wrote in his memoirs: “As our long range guns were pounding the Russian positions in a way to cut their ammunition supplies, headquarters and roads from one side to the other, Russians returned fire throughout the day. When it was evening, the gun fire slowed down. The enemy fired gas shells at the German positions on our left flank, however they did not cause any harm… On the night of 12/13 July a major bombardment against the enemy was started with the participation of German, Austrian and Hungarian units of all sizes… It was like the skies were tearing apart. As the shelling was going on, at around two o’clock were ordered to reinforce the German positions at Kurzhani. We departed immediately and arrived in the German headquarters.”

On 15 July, the headquarters of the XV Army Corps departed from Galicia by train en route to Istanbul. The Rohatyn Group assumed command of the 20th Division. Given the futility of their attempts to advance and break through the Turkish defensive line, the Russians opted for a strategic retreat. They vacated their positions, evacuated the towns and villages they had occupied, and commenced an eastward movement. On 21 July, the 20th Division received orders to pursue the retreating Russian forces in collaboration with the German South Army, with the objective of eliminating Russian units situated between the rivers Dniester and Sereth.

The pursuit commenced the following day, during which an inspection was conducted by Kaiser Wilhelm, who conveyed his appreciation. The Russians encountered challenges in establishing a defensive line east of the Zebruc River, while Turkish and German forces sought to cross the river. At this juncture, an order was issued instructing the Turkish division to halt, refrain from crossing the river, and prepare to return to Turkey.

On 5 August, the Turkish 20th Division was relieved by the German 24th Division and subsequently withdrawn to staging areas situated behind the lines and adjacent to rail terminals. Ceremonies and medal presentations were conducted in preparation for departure. The artillery units departed on 16 August, followed by the infantry units on 22 August. By 26 September 1917, all units of the 20th Division had returned to Istanbul.

In the Turkish tradition, the justification and glorification of war stem from its perceived role in safeguarding the homeland. However, such motivations did not align with the circumstances in Galicia. The Galician campaign, in contrast, represented an expedition driven by strategic considerations, specifically an economy of manpower mission, allowing the Germans to redirect their forces elsewhere. Presently, the recollection of the Galician campaign among the Turkish populace does not categorize it as an "unnecessary war"; rather, it receives comparatively less attention than the renowned epic of Gallipoli or the tragic events of Sarıkamış, where the imperative of homeland defence took precedence.

The Galician campaign marked a significant historical juncture as the first instance of the Turkish army engaging in foreign conflict under the command of allied powers. This episode showcased the formidable capabilities of Turkish soldiers when adequately equipped and supplied. In Galicia, the Turkish XV Army Corps incurred an overall casualty count of approximately 25,000, with an additional 10,000 Turkish soldiers becoming prisoners of war in Russian custody. Subsequently, these captives were deported to distant locales such as Kazan, Moscow, and Siberia.

![]()

Sources consulted:

- Ertem, Ş., “Avrupa’da Yüz Bin Türk Askeri” (Hundred Thousand Turkish Soldiers in Europe), Kastaş Yayınları, Istanbul, 1992.

- Yazman, M.Ş., “Kumandanım Galiçya Ne Yana Düşer?” (Commander, Where on the Earth is Galicia?), İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, Istanbul, 2007. (edited by Şarman, K. from the original text “Mehmetçik Avrupa’da” (Mehmetçik in Europe) published first in Istanbul, 1928)

- Official History, “Birinci Dünya Savaşı’nda Türk Harbi – Avrupa Cepheleri” (Turkish Battles in the First World War – European Fronts), Genelkurmay Yayınları, Ankara, 1996.

PAGE LAST UPDATED ON 29 NOVEMBER 2023