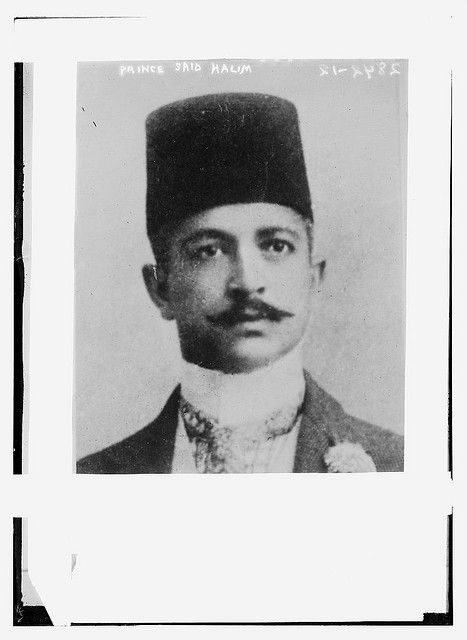

Mehmet Sait Halim was born on February 19, 1864 in Cairo. His grandfather was Mehmet Ali Paşa, a viceroy of Egypt who had rebelled against the Sultan. He came to Istanbul with his family when he was six years old. He learned Arabic, Persian, French, English and he studied political science in Switzerland. Upon his return to Istanbul he became a member of the State Council in 1888 and he was appointed as the governor of Rumeli in 1890.

Mehmet Sait Halim was born on February 19, 1864 in Cairo. His grandfather was Mehmet Ali Paşa, a viceroy of Egypt who had rebelled against the Sultan. He came to Istanbul with his family when he was six years old. He learned Arabic, Persian, French, English and he studied political science in Switzerland. Upon his return to Istanbul he became a member of the State Council in 1888 and he was appointed as the governor of Rumeli in 1890.

Sultan Abdülhamid sent Sait Halim to exile, when it was found out that he had links with the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). He first went to Egypt and then moved to Europe where he had contact with the CUP for which he was also providing financial assistance.

Sait Halim returned to Istanbul when the constitutional rule was proclaimed in 1908. Four years later he became the chairman of the State Council. He left this post after a government change, but only to be reinstalled again when Mahmut Şevket Pasha became Grand Vizier. He also had a place in the cabinet, as the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

When Mahmut Şevket Pasha was assassinated, the CUP asked him to become the Grand Vizier, he accepted it, although the Sultan was against this appointment. In this capacity, he negotiated peace conditions with the Balkan nations.

It is still a question, whether Sait Halim Pasha approved Turkey’s entry to the World War or even whether he was informed about it in advance. The fact is that during the course of the war, he diverged from the CUP leaders. He resigned on February 3, 1917.

After the armistice, the military tribunal found him guilty and Sait Halim Pasha was sent to exile in Malta. He was released on April 29, 1921 and he crossed over to Sicily. From there, he wanted to return to Istanbul but he did not manage to obtain the approval of Ankara government.

On December 6, 1921, he was assassinated by an Armenian gunman in front of his apartment in Rome. His remains were brought to Istanbul and buried at the Tomb of Sultan Mahmut.

Sait Halim Paşa was not only a politician, but also a leading thinker of his time and an opponent of the ideology of modernisation. He was not against the Ottoman-Islamic modernisation itself, but he was opposing its content and direction. He thought that it was wrong for reform movements to ignore the interactions between religious, political, social and cultural spheres, which can affect different societies with different backgrounds in different ways. For him it was wrong to imitate the Western progress as it is.

![]()