Propaganda has been a crucial component in the war efforts of all the belligerents of the First World War. As a form of communication aimed at influencing the attitude of communities towards war aims, propaganda has usually appeared in the shape of graphic arts (cartoons, illustrations, postcards), stage performances or movies. Combining visual imagery and performance, movies have been particularly influential in conveying patriotic ideas thanks to their appeal to larger masses.

In this essay, we will have a look at how Imperial Russia used movies as a tool of propaganda against the Ottoman Empire. There have been a number of movies in this respect, which, although having different story-lines, shared some common features:

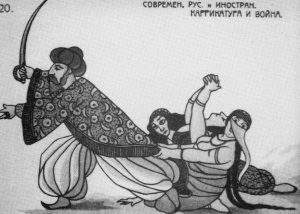

* They all have a strongly orientalist perspective, depicting early 20th century Ottoman Empire as a place from the Tales of 1001 Nights, complete with harems and eunuchs.

* Turks are always depicted as ugly, weak, and coward beings, most often with sexual addiction.

* Turks are regarded to as the lesser enemy, who matter only as the partner of the greater enemy, i.e. Germany.

The most popular anti-Turkish propaganda movie was “Enver Pasha – Traitor of Turkey” (Enver pasha – predatel’ Turtsii / Энвер-Паша - Предатель Турции). This movie, directed by Protazanov, with actor Vladimir Maximov playing Enver Pasha, was released in 1915, as fighting was going on in the Caucasian front between the Turks and Russians.The film drew largely on actual events surrounding Turkey’s entry into the war, combined with fictitious stories related to Enver Pasha’s life. The story begins in pre-war Berlin, where Enver is working at the Ottoman Embassy as a military attaché. He is an influential member of the Young Turks and he is courted by Kaiser Wilhelm, who honours him in order to ensure his loyalty in the coming war. Enver falls in love with Alisa, the girlfriend of one of Wilhelm’s adjutants, but when the Balkan War breaks out, the patriotic young Enver leaves Germany and Alisa for his duty. By 1914, he has become the most powerful man in Istanbul. The German General Liman von Sanders tries to persuade him to ally with Germany, but Enver refuses, because he is afraid of Russia’s might! Then Germans then play a trick and send Alisa to Istanbul to talk Enver into the war.

The most popular anti-Turkish propaganda movie was “Enver Pasha – Traitor of Turkey” (Enver pasha – predatel’ Turtsii / Энвер-Паша - Предатель Турции). This movie, directed by Protazanov, with actor Vladimir Maximov playing Enver Pasha, was released in 1915, as fighting was going on in the Caucasian front between the Turks and Russians.The film drew largely on actual events surrounding Turkey’s entry into the war, combined with fictitious stories related to Enver Pasha’s life. The story begins in pre-war Berlin, where Enver is working at the Ottoman Embassy as a military attaché. He is an influential member of the Young Turks and he is courted by Kaiser Wilhelm, who honours him in order to ensure his loyalty in the coming war. Enver falls in love with Alisa, the girlfriend of one of Wilhelm’s adjutants, but when the Balkan War breaks out, the patriotic young Enver leaves Germany and Alisa for his duty. By 1914, he has become the most powerful man in Istanbul. The German General Liman von Sanders tries to persuade him to ally with Germany, but Enver refuses, because he is afraid of Russia’s might! Then Germans then play a trick and send Alisa to Istanbul to talk Enver into the war.

Alisa would not succeed either. In this movie, Enver has a big harem inside his phantasmagoric castle (remember this is an orientalist Russian movie) and Alisa’s arrival makes Enver’s favourite concubine jealous. She searches Alisa’s belongings and finds a letter revealing the German girl’s mission. She gives the letter to Enver, who realises that he has become a tool in the hands of the Germans! He sends a eunuch to kill Alisa and at the same time he sees a nightmare: Turkey is destroyed in a war with the mighty Russia and a golden cross appears at the top of the mosque of Ayasofya (Hagia Sophia).

This is a very interesting movie, and it can be said actually that its real target is not Turkey but Germany. Turkey is shown as a weak country, which is deceived by the real devil, Germany. On the other hand Russia is strong, has superior morality and civilisation. It can even be said that what the movie aims at is to convey a message to the Turks telling them that it is the Russians who are they real friends (and who should be their allies) and not the Germans.

Although these movies are anti-Turkish (and of course anti-German) propaganda, there is always a certain level of sympathy towards the Turks or at least there exists one sympathetic Turkish figure. Most of the times the Russian directors cannot hide their fascination with oriental stereotypes.

In the movie “Turkish Espionage: The War and the Woman” (Turetskii spionazh: voina i zhenshschina / Туретскии спионаж: воина и женшчина), released by Libken in 1915, a young French girl who has learned to fly a plane falls in love with a Serbian pilot. She joins the International Red Cross so that she can be close to him, and she is sent to a Turkish hospital. She takes care of a wounded Turkish officer, who happens to be a friend of the man she loves. As the Turkish officer is lying in his bed unconsciously, she searches his pockets and finds the plans for a major Turkish offensive! She tries to run away, but fails in her attempt and lands in a Turkish dungeon. She tries once again, this time wearing the uniform of a fallen Turkish officer, whose documents she uses to get through the lines and to commandeer a Turkish airplane. She flies over the frontline, arrives in Serbian positions and informs them about the coming attack. Serbia manages to repel the Turkish attack and young lovers get married. This movie shows how technology and modern woman win over the not-so-modern Turkish male brutality.

Another leading female role appears in the movie “The Bloody Crescent” (Krovavyi polumesiats / Кровавый полумесяц), which was produced by Drankov. This movie focuses on the sufferings of a Russian girl in an Ottoman harem. Turks are shown as silly and weak beings, deceived by the real enemy of Russia, which is Germany.

Russians also shot movies focusing on their successes in the battlefield. One such film was about the capture of the Turkish town of Erzurum "The Storming and Capture of Erzurum" (Sturm i zahvata Erzuruma / Штурм и захвата Эрзурума).The film, did not show any battle scenes, instead there were long marches of Russians troops under snow and hordes of Cossack cavalry riding towards the city. Erzurum itself is shown like in a documentary, with the camera showing a series of Armenian churches, Turkish mosques and destroyed houses in sequence. At the end of the film, Russia is shown as a proud woman in a boyar costume and a soldier sitting at her feet holding a flag bearing the Turkish crescent and the inscription “Erzurum”, shouting “God Save the Tsar”. This move was not only propaganda but it was also kind of a documentary aiming to show the Russian audience the daily lives of Russian soldiers and the scenic spots from captured territories.

Most of the information about the movies are taken from an excellent book by Hubertus F. Jahn, titled “Patriotic Culture in Russia During World War I” (Cornell University Press, 1995). We would also like to thank Natalia Alexandrovna Timoshina for drawing our attention to these movies and providing visual material.