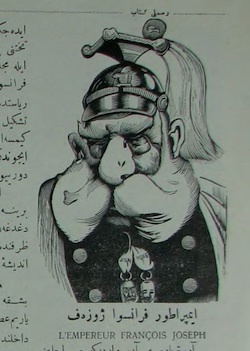

The Ottoman Empire had entered the twentieth century in a state of political fragility, territorial contraction, and economic vulnerability. Faced with the loss of its Balkan territories, the rise of nationalist movements, and increasing pressure from European powers, the empire was acutely aware of the need for external support to safeguard its remaining territories. Austria-Hungary, in contrast, faced its own set of existential challenges. The multinational empire struggled to contain nationalist dissent within its borders while maintaining dominance in the Balkans, a region increasingly threatened by Serbian expansionism and Russian influence. The convergence of these pressures created a natural, if uneasy, alignment of interests between the two empires.

The Ottoman Empire had entered the twentieth century in a state of political fragility, territorial contraction, and economic vulnerability. Faced with the loss of its Balkan territories, the rise of nationalist movements, and increasing pressure from European powers, the empire was acutely aware of the need for external support to safeguard its remaining territories. Austria-Hungary, in contrast, faced its own set of existential challenges. The multinational empire struggled to contain nationalist dissent within its borders while maintaining dominance in the Balkans, a region increasingly threatened by Serbian expansionism and Russian influence. The convergence of these pressures created a natural, if uneasy, alignment of interests between the two empires.

The Ottoman-Austrian alliance was therefore grounded in pragmatic considerations rather than deep-seated ideological affinity. Austria-Hungary sought to secure Ottoman cooperation to stabilize its southern flank and to complement its military efforts against Serbia and, indirectly, Russia. For the Ottomans, an

galliance with Austria-Hungary offered the prospect of political legitimacy, military assistance, and a diplomatic counterweight to the growing influence of the Entente powers. This partnership was further shaped by Germany’s overarching influence over the Central Powers, which both constrained and facilitated Ottoman-Austrian coordination, adding layers of complexity to the diplomatic and military interactions between the two empires.

Although often overshadowed by the more prominent German-Ottoman alliance, the Ottoman-Austrian partnership had tangible consequences on the course of the war. It affected strategic decisions in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, influenced Ottoman domestic and foreign policy, and contributed to the broader Central Powers’ war effort. The alliance also reflected historical patterns of interaction between the two empires, combining centuries of rivalry with moments of pragmatic cooperation, particularly in the face of shared external threats.

Historical Background

The Ottoman and Austrian empires shared a long and often hostile history, primarily centered on control over the Balkans and Central Europe. Their conflicts spanned several centuries, beginning in the 16th century as the Ottomans expanded into Hungary and Habsburg territories, including the significant sieges of Vienna in 1529 and 1683. Other notable confrontations occurred between 1593–1606 and 1716–1718, each reshaping territorial control and limiting Ottoman influence in Central Europe. Even in the 18th and 19th centuries, periodic clashes over frontier regions, including Bosnia and Dalmatia, continued to define the balance of power, reinforcing mutual distrust and rivalry. These conflicts were driven by territorial ambitions, religious divisions, and strategic considerations, with Austria seeking to expand southward and Ottoman rulers striving to secure their European holdings.

Despite these conflicts, both empires also engaged in periods of cautious diplomacy, trade, and strategic accommodation, particularly as pressures from Russia and other European powers intensified in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Economic ties, particularly trade along the Danube and the Adriatic, and political interactions in the context of the “Eastern Question” became more prominent. A long history of warfare and negotiation created a complex backdrop of rivalry, pragmatism, and strategic calculation that informed their interactions leading up to the First World War.

By the early 20th century, Austria-Hungary faced mounting internal and external pressures. Its multinational composition, with significant Slavic, Magyar, and German populations, made domestic governance increasingly challenging. Nationalist movements, particularly among Serbs and other South Slavs, threatened the cohesion of the empire, while Russia’s support for pan-Slavic aspirations in the Balkans amplified the sense of vulnerability. The annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908 had already provoked tensions with Serbia and Russia, highlighting the precariousness of Austria-Hungary’s position.

Strategically, Austria-Hungary required allies who could provide military and diplomatic support to secure its southern borders and to maintain influence in the Balkans. The Ottoman Empire, despite its own decline, presented a potential partner whose geographic position and strategic interests in the Eastern Mediterranean could complement Austrian objectives. An alignment with the Ottomans could serve as a counterweight to both Russian expansionism and Balkan nationalist movements, creating a more favorable environment for Austria-Hungary’s security concerns.

For the Ottoman Empire, on the other hand, the early 20th century was a period of existential uncertainty. The empire had lost nearly all of its Balkan territories in the wars of 1912–1913, its economic resources were stretched thin, and political authority was fragmented between the sultan, the Committee of Union and Progress, and regional elites. Facing both internal instability and external encroachment, the Ottomans were acutely aware of their need for reliable alliances to safeguard their remaining territories and to maintain sovereignty over Anatolia and strategic Middle Eastern regions.

The Ottoman leadership recognized that engagement with European powers could provide both military and diplomatic leverage. An alliance with Austria-Hungary, whose concerns over Balkan stability closely mirrored Ottoman interests, offered a strategic opportunity. While the empire also considered alignment with Germany and even maintained cautious relations with the Entente powers, the Austro-Ottoman partnership presented a pragmatic avenue for counterbalancing Russian influence and reinforcing the empire’s security in a highly volatile geopolitical environment.

Formation of the Alliance

Diplomatic engagement intensified in the months leading up to the outbreak of the First World War. Austria-Hungary sought Ottoman support to stabilize its southern flank in the Balkans, particularly given the volatile situation in Serbia and the threat of Russian intervention. Ottoman leaders, including Enver Pasha, recognized the potential benefits of alignment without compromising sovereignty, while Austrian advisors such as Josef Pomiankowski facilitated understanding of Ottoman military and political structures.

With the outbreak of war, Pomiankowski, already a Generalmajor, became head of the Austro-Hungarian military mission in the Ottoman Empire, effectively serving as the junior partner to the German military mission under Otto Liman von Sanders. In this capacity, Pomiankowski sought to use tensions between German and Ottoman interests to assert Austrian political and economic influence in the Orient, despite limited resources. Working closely with Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Leopold Berchtold and Ambassador Johann Markgraf Pallavicini, he aimed to pursue an independent Austrian Orient policy—effectively striving for a condominium over the Ottoman Empire, in full equality with Germany.

Negotiations were characterized by cautious pragmatism. Both sides were aware of historical mistrust stemming from centuries of conflict and sought to balance cooperation with strategic autonomy. Austria-Hungary emphasized the shared interest in countering Slavic nationalism and Russian influence, while Ottoman diplomats secured assurances that engagement would not lead to unwanted entanglements. Germany, through figures such as General Liman von Sanders, mediated this alignment, enhancing coordination while ensuring adherence to broader Central Powers strategy.

Pomiankowski’s role extended beyond the military. He actively shaped Austrian Orient policy, acting as diplomat, intelligence chief, propagandist, cultural ambassador, and economic advisor. In 1917, he pushed for the establishment of an “Orient Department” within the War Ministry to safeguard Austria-Hungary’s economic and strategic interests in the Balkans and Ottoman territories, preventing Germany from monopolizing influence. He also critically assessed Ottoman society, attributing structural difficulties in modernization to the constraints of Islam and opposing German attempts to mobilize Muslims via pan-Islamic jihad, which he viewed as impractical due to religious fragmentation.

Unlike the more formalized German-Ottoman alliance, the Austro-Ottoman partnership initially developed in a less codified but nonetheless operationally significant form. Early agreements were largely based on military understandings, joint strategic planning, and reciprocal diplomatic support. Austria-Hungary provided military advice and logistical assistance, while both empires coordinated their efforts to ensure that their forces could operate in complementary theaters. Key elements of this cooperation included coordination in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, consultation on military deployments, and mutual recognition of territorial priorities.

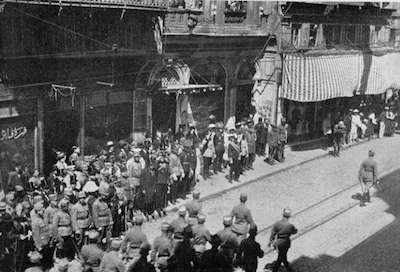

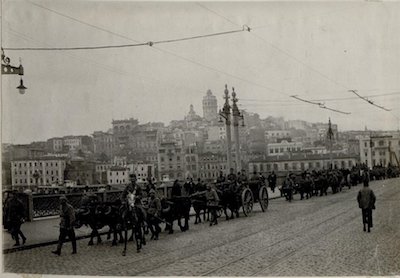

The formalization of the Austro-Ottoman alliance occurred later in the war. Following the accession of Emperor Karl, Austria-Hungary officially joined the defensive pact initially negotiated between Germany and the Ottoman Empire in January 1915. The secret treaty, signed on 22 March 1917 by Ambassador Johann Markgraf Pallavicini and Grand Vizier Talat Pasha and ratified by Emperor Karl on 18 April 1917 in Laxenburg, marked a significant milestone in Austro-Ottoman cooperation. This diplomatic alignment was further symbolized by Emperor Karl and Empress Zita’s official visit to Istanbul in May 1918, underscoring both the strategic importance and ceremonial recognition of the partnership.

The Ottoman-Austrian alliance existed within the broader framework of the Central Powers, in which Germany played a leading role. Germany’s influence was crucial in aligning Ottoman and Austrian interests, as Berlin sought to maximize cohesion among its allies and to prevent independent Austrian or Ottoman initiatives from undermining overall strategy. Germany’s role was twofold. First, it acted as a mediator, facilitating communication and ensuring that Austro-Ottoman coordination did not conflict with German military plans on the Eastern Front and in the Middle East. Second, German military advisors and officers often served as intermediaries in operational planning, ensuring that Austro-Ottoman cooperation adhered to the broader objectives of the Central Powers. This trilateral dynamic, while enhancing coordination, also introduced constraints, as both Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire had to balance their national priorities with Germany’s strategic vision.

Military Cooperation and Strategic Coordination

The military dimension of the Ottoman-Austrian alliance was central to its practical significance during the First World War. While diplomatic agreements and strategic understandings provided the framework, the effectiveness of the alliance was ultimately measured by operational coordination, joint planning, and the capacity to respond to shared threats. This cooperation, though limited compared to the German-Ottoman partnership, manifested across multiple theaters and reflected both the opportunities and challenges of coordinating two empires with distinct military traditions and capabilities.

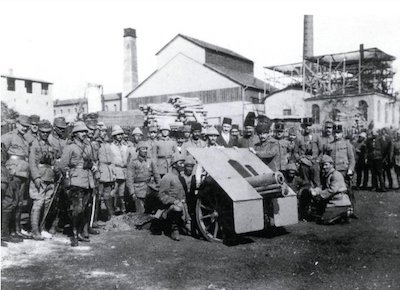

During the winter of 1915, Austro-Hungarian artillery batteries played a critical role alongside Ottoman forces in defending the Gallipoli Peninsula against massive Allied attacks. The effective use of heavy artillery, combined with logistical support from Austro-Hungarian motorized units, field hospitals, and experimental long-range wireless communication, demonstrated the practical value of the alliance in sustaining Ottoman defensive operations. These efforts, though ultimately delaying the inevitable advance of British forces from Egypt, exemplified the Austro-Ottoman capacity for operational collaboration under difficult circumstances. Austrian units also benefitted from the cooperative disposition of Ottoman leadership, with Enver Pasha allocating several infantry divisions to reinforce Austro-Hungarian positions on the Eastern Front.

The Balkans were a primary zone of concern for Austria-Hungary, whose southern flank was vulnerable to Serbian nationalist ambitions and Russian influence. The Ottoman Empire, while geographically distant from many of the key Balkan battlefields, had an interest in the region due to its historical ties, the legacy of the Balkan Wars, and the presence of Muslim populations sympathetic to Ottoman influence.

Ottoman support for Austria in the Balkans primarily took the form of intelligence sharing, advisory roles, and logistical assistance, rather than large-scale troop deployments. Austrian planners valued Ottoman knowledge of terrain, local political conditions, and regional networks, which could be leveraged for operations against Serbia and in coordinating defenses against potential Entente incursions. This collaboration enhanced Austria-Hungary’s operational confidence in the region, even if direct Ottoman combat involvement was relatively limited.

On the Eastern Front, both empires faced the strategic threat posed by Russia. Austria-Hungary bore the brunt of fighting against Russian forces in Galicia and along the Carpathians, while the Ottoman Empire, aligned with Germany, was increasingly concerned about potential Russian advances into Anatolia and the Caucasus.

Ottoman defensive operations in Mesopotamia and Palestine also benefited from Austro-Hungarian logistical advice and German mediation. While Austrian officers did not participate directly in combat, they assisted in troop deployments, rail coordination, and fortification planning, indirectly supporting Ottoman military efforts.

Military coordination between the two empires involved careful strategic planning to ensure that Austro-Hungarian operations in Eastern Europe did not inadvertently weaken the Ottoman position against Russia. Austro-Ottoman discussions, often mediated by German officers, addressed troop movements, timing of offensives, and defensive postures. While direct joint operations were rare due to geographic separation, the alignment of strategic objectives and sharing of intelligence contributed to a more coherent Central Powers approach on these fronts.

A critical aspect of the alliance was the exchange of military expertise, logistical support, and technical knowledge. Austria-Hungary supplied military advisors, maps, and technical assistance to Ottoman forces, particularly in areas such as artillery coordination, fortification design, and railway logistics. Conversely, Ottoman officials facilitated access to regional transport networks and provided guidance on local terrain conditions in strategic areas.

This cooperation also included indirect coordination through German intermediaries. Austro-Hungarian officers occasionally collaborated with German advisors to train Ottoman units, streamline supply chains, and optimize troop deployments. While the scale of assistance was modest relative to German support, it demonstrated the practical dimension of Austro-Ottoman collaboration and underscored the empire’s shared interest in sustaining each other’s military capabilities.

Despite these efforts, military cooperation faced significant limitations. Geographic separation, divergent military traditions, and differing command structures complicated coordination. Communication delays and bureaucratic inefficiencies further hindered rapid operational alignment. Additionally, Austria-Hungary’s preoccupation with its Balkan campaigns limited the resources and attention it could devote to the Ottoman theater, while Ottoman commanders often prioritized local defensive concerns over broader Central Powers strategies.

Nonetheless, even within these constraints, the alliance provided a framework for strategic dialogue, mutual support, and operational alignment. It reflected the pragmatic recognition by both empires that coordinated effort, however limited, was preferable to unilateral action in the context of a multi-front global conflict.

Political and Diplomatic Dimensions

Beyond the battlefield, the Ottoman-Austrian alliance had significant political and diplomatic implications. It was not solely a military arrangement but also a strategic partnership shaped by shared geopolitical interests, domestic considerations, and the complex interplay of European power politics. Both Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire sought to contain Russian expansion and to mitigate the influence of nationalist movements within and around their borders. For Austria-Hungary, maintaining control in the Balkans was vital to the empire’s territorial integrity, while the Ottomans aimed to secure their remaining European and Anatolian territories.

The partnership allowed the two empires to coordinate positions on critical geopolitical issues, from the management of contested Balkan regions to the handling of the Dardanelles and the Eastern Mediterranean. This alignment extended to broader Central Powers diplomacy, where Austro-Ottoman cooperation complemented German strategic initiatives, creating a network of mutual support against the Entente powers.

The alliance also had implications for internal Ottoman politics. The Committee of Union and Progress, which had consolidated power after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, sought to navigate a delicate balance between external alliances and domestic stability. Austrian support, alongside German influence, reinforced the Committee’s position by providing a sense of external backing against both Entente pressures and internal opposition.

At the same time, the alliance required the Ottomans to carefully manage public perception and political messaging. Cooperation with Austria-Hungary, a former adversary, had to be framed in terms of pragmatic strategy rather than historical enmity, ensuring that the partnership did not undermine domestic legitimacy or provoke unrest among populations with lingering memories of past conflicts.

The alliance existed within a broader diplomatic environment characterized by intense negotiation and competition among European powers. Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire both had to navigate relations with Germany, whose influence over the Central Powers was dominant, as well as Bulgaria and other regional actors.

The partnership also shaped interactions with neutral countries and the Entente. Coordinated Austro-Ottoman positions strengthened Central Powers claims in diplomatic negotiations and served as a counterweight to Entente influence in the Balkans and the Eastern Mediterranean. By aligning their diplomatic strategies, the two empires amplified their international presence and enhanced the credibility of their mutual commitments, even when direct military coordination was constrained.

Despite shared interests, the alliance faced inherent diplomatic challenges. Austria-Hungary’s primary concern with Balkan stability sometimes diverged from Ottoman priorities in the Middle East and Anatolia. Additionally, both empires had to reconcile their individual strategies with Germany’s overarching control of Central Powers policy, which occasionally limited the flexibility of bilateral decision-making.

Nevertheless, these challenges did not negate the alliance’s political utility. Even when divergences arose, the framework of cooperation facilitated dialogue, intelligence exchange, and coordination in both wartime planning and international diplomacy, reinforcing the strategic interdependence of the two empires.

Strains and Diverging Priorities

By 1917, the Ottoman-Austrian alliance, while functional, began to reveal the limits of its effectiveness. As the war progressed, both empires faced intensifying military pressures, domestic challenges, and shifting geopolitical circumstances. These factors exposed divergences in strategic priorities, operational capabilities, and diplomatic agendas, placing strain on the partnership and testing the resilience of Central Powers coordination.

One of the most pressing sources of tension was the difference in strategic priorities between the two empires. Austria-Hungary remained primarily focused on maintaining control in the Balkans and defending its northern and western fronts against Entente advances. In contrast, the Ottoman Empire was increasingly preoccupied with safeguarding its Middle Eastern territories, particularly in Mesopotamia, Palestine, and the Caucasus, from British and Russian offensives.

This divergence often resulted in conflicting demands on Central Powers resources and attention. While Austria-Hungary sought Ottoman support for Balkan operations, the Ottomans were constrained by commitments elsewhere, including the defense of key strategic positions and the management of internal security. These differing priorities created friction in operational planning, highlighting the limitations of the alliance in coordinating multi-theater campaigns effectively.

The geographic distance between the two empires compounded strategic conflicts with logistical and operational difficulties. Direct military coordination was hindered by transportation limitations, communication delays, and the challenge of integrating disparate military systems. Austria-Hungary, already stretched by protracted engagements on multiple fronts, found it difficult to provide timely support or to fully synchronize with Ottoman operations. Similarly, Ottoman forces, despite the presence of Austrian advisors and intelligence sharing, struggled to align their actions with Austrian objectives due to local constraints and resource scarcity.

These operational challenges underscored the practical limits of the alliance. While the partnership enabled dialogue and strategic consultation, it could not fully overcome the realities of wartime distance, logistical complexity, and the divergent theaters in which each empire was engaged.

Diplomatic divergences also emerged during this period. Austria-Hungary increasingly relied on Germany to mediate differences and ensure Central Powers cohesion, while the Ottoman leadership sought to maintain a degree of autonomy in its foreign policy decisions. These dynamics occasionally resulted in tensions, particularly when Ottoman interests in the Middle East appeared to conflict with Austrian goals in the Balkans or German operational plans.

Internal pressures within both empires further complicated the relationship. Austria-Hungary faced mounting nationalist unrest and declining morale, while the Ottoman Empire contended with political factionalism, economic strain, and the challenges of mobilizing an overstretched military. These domestic pressures influenced each empire’s ability to commit fully to joint initiatives, revealing the fragility of the alliance under sustained stress.

The broader developments of the war accelerated the strains in the alliance. Military setbacks on multiple fronts, including the defeat of Austria-Hungary in Italy and pressure on Ottoman positions in Palestine and Mesopotamia, shifted the balance of strategic urgency. Both empires were forced to prioritize immediate survival over coordinated long-term planning, which limited the practical value of the alliance in the final years of the conflict.

Despite these challenges, the alliance continued to function at a basic level, facilitating strategic consultation, intelligence exchange, and diplomatic support. However, the diverging priorities and operational constraints revealed that the Ottoman-Austrian partnership was ultimately contingent, dependent on immediate pragmatic needs rather than a deep, institutionalized commitment.

Consequences and Legacy

The alliance contributed to Central Powers cohesion, providing a framework for intelligence, logistics, and strategic consultation. Its tangible military impact was limited by divergent theaters, operational constraints, and domestic pressures. Postwar, Austria-Hungary dissolved, and the Ottoman Empire faced territorial partition. Despite its fragility, the alliance illustrated the benefits of pragmatic cooperation between declining empires, influencing interwar diplomacy and regional politics. Historiographically, it offers insight into coalition warfare, operational adaptation, and the interplay of strategy, diplomacy, and operational reality.

The Austro-Ottoman alliance must be understood within the broader framework of the Central Powers, where Germany served as the strategic coordinator and principal military partner. While the Austro-Ottoman relationship operated with a degree of autonomy, it was always intertwined with the German-Ottoman alliance. Germany’s influence shaped operational planning, resource allocation, and diplomatic alignment, ensuring that bilateral Austro-Ottoman initiatives complemented overall Central Powers objectives rather than undermining them.

The German-Ottoman partnership, often more visible due to the scale of German military missions, the direct involvement of officers such as Liman von Sanders, and Germany’s decisive role in theaters such as Gallipoli and Mesopotamia, set the strategic tone for Ottoman participation in the war. Austria-Hungary, although less dominant, contributed meaningfully by providing military advice, logistical support, and intelligence, particularly in areas where Germany could not fully intervene. In this way, the Austro-Ottoman alliance supplemented German efforts, enhancing operational flexibility and offering the Ottomans additional channels of coordination.

The trilateral dynamic among Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire also reflected the complexities of coalition warfare among empires with differing priorities, capacities, and strategic visions. While Germany sought centralized control to maximize coherence and effectiveness, Austria-Hungary pursued regional influence in the Balkans, and the Ottomans navigated defense of their Middle Eastern territories alongside domestic political considerations. This balancing act created both opportunities for coordinated strategy and points of tension, requiring constant negotiation, mediation, and compromise.

In practical terms, the Austro-Ottoman collaboration allowed the Ottoman Empire to benefit from a broader support network, not solely reliant on Germany, while Austria-Hungary could indirectly influence Ottoman decisions and secure its southern flank. The partnership contributed to operational resilience, particularly in managing multi-theater campaigns and responding to localized crises. While it did not yield decisive military victories, the alliance provided essential consultation, technical assistance, and strategic coherence, strengthening the Central Powers’ collective position.

Ultimately, the Austro-Ottoman alliance underscores the interplay between strategic necessity, diplomatic pragmatism, and operational reality within a larger coalition. It illustrates how empires with divergent priorities and capabilities could still align their interests in the context of a global conflict, mediated by a dominant partner. The relationship also highlights the limits of coalition warfare: geographic distance, domestic pressures, and competing priorities constrained operational integration, yet pragmatic collaboration enhanced the resilience and strategic flexibility of both empires within the Central Powers network. The Austro-Ottoman partnership, therefore, complements the narrative of German-Ottoman cooperation, offering a fuller understanding of the interdependent alliances that defined the Central Powers’ wartime strategy.

![]()

PAGE LAST UPDATED ON 13 SEPTEMBER 2025