Throughout much of the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire maintained a delicate balance between the Great Powers of Europe, relying primarily on Britain and France to counterbalance the Russian threat. The Crimean War had demonstrated the extent of Anglo-French support, as both powers intervened militarily to prevent Russian expansion into Ottoman territories. However, the Ottoman reliance on Britain and France also deepened its financial dependence. By the 1860s, a series of costly military campaigns, coupled with large-scale infrastructure projects, left the empire burdened with immense debt, ultimately leading to financial insolvency in 1875. In response, European creditors established the Ottoman Public Debt Administration (Düyûn-u Umûmiye) in 1881, placing significant portions of the empire’s revenues under foreign control. These developments gradually eroded Ottoman sovereignty and sowed distrust toward Britain and France, creating an opening for new alliances.

Throughout much of the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire maintained a delicate balance between the Great Powers of Europe, relying primarily on Britain and France to counterbalance the Russian threat. The Crimean War had demonstrated the extent of Anglo-French support, as both powers intervened militarily to prevent Russian expansion into Ottoman territories. However, the Ottoman reliance on Britain and France also deepened its financial dependence. By the 1860s, a series of costly military campaigns, coupled with large-scale infrastructure projects, left the empire burdened with immense debt, ultimately leading to financial insolvency in 1875. In response, European creditors established the Ottoman Public Debt Administration (Düyûn-u Umûmiye) in 1881, placing significant portions of the empire’s revenues under foreign control. These developments gradually eroded Ottoman sovereignty and sowed distrust toward Britain and France, creating an opening for new alliances.

A turning point came with the Congress of Berlin in 1878, which reshaped Ottoman relations with Europe. While the congress prevented excessive Russian gains, it also resulted in major territorial losses: Bosnia and Herzegovina were occupied by Austria-Hungary, Britain took control of Cyprus, and Bulgaria became effectively autonomous. The outcome left the Ottomans humiliated and disillusioned, particularly since Britain and France, long considered allies, had played active roles in their weakening. From this point onward, Ottoman leaders increasingly viewed Germany as a potential partner, precisely because Berlin had no territorial ambitions against the empire.

For Germany, too, the late 19th century presented a new opening. Unlike Britain, France, and Russia, it lacked extensive colonial possessions and could not easily expand in Africa or Asia. Ottoman lands, rich in resources and strategically located, offered a rare sphere where Germany could build influence without provoking colonial rivalries. Instead of seeking annexations, German policymakers emphasized military cooperation and economic investment, approaches that resonated with an empire weary of foreign encroachments yet unable to resist them outright.

German interest in Ottoman affairs, however, had earlier roots. Even in the Prussian era, figures such as Frederick the Great explored cooperation with the Ottomans, while Helmuth von Moltke’s service in the 1830s left behind detailed observations on the empire’s strategic value. Around the same time, German economists like Friedrich List argued that the Balkans and the Middle East could become vital sources of power for Germany if modernized with German expertise. Such early visions encouraged Berlin to look toward the Ottoman world as the European balance of power shifted.

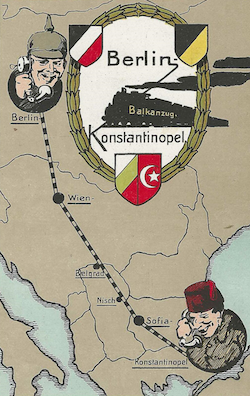

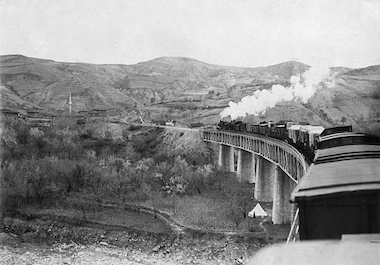

The first concrete steps toward closer ties came in the 1880s. Sultan Abdulhamid II invited a German military mission to Istanbul under General Colmar von der Goltz, whose reforms reshaped the Ottoman officer corps along Prussian lines. These efforts were well received, as many Ottomans increasingly distrusted the British and French. At the same time, German firms moved into infrastructure and heavy industry, culminating in the Berlin–Baghdad Railway, financed by Deutsche Bank. This project symbolized Germany’s approach of building long-term influence through economic integration rather than colonial conquest.

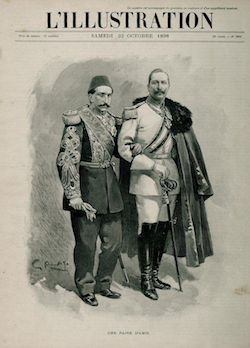

Kaiser Wilhelm II further strengthened the relationship through personal diplomacy. Unlike Bismarck, he was eager to expand German presence in the Middle East. His visits to the Ottoman Empire, combined with his highly publicized declarations of friendship toward the Muslim world, stood in stark contrast to the imperial ambitions of Britain, France, Russia, and Italy. To many in Istanbul, Germany thus appeared not as a predator but as a partner, one of the few great powers that could be welcomed without fear of outright domination.

By the end of the 19th century, Germany had firmly established itself as the Ottoman Empire’s closest strategic ally. Military reform, economic investment, and personal diplomacy combined to create a partnership based less on colonial control and more on mutual need. While Britain and France still dominated Ottoman finances, Germany had secured a privileged role as the empire’s military and political supporter. These foundations would set the stage for the formal Ottoman–German alliance during the First World War.

Political and Ideological Factors

The Ottoman Empire was at a crossroads, as it was struggling with administrative inefficiencies, nationalist uprisings, and economic difficulties at home, while at the same time it faced continuous territorial losses and the growing ambitions of European powers eager to carve out their own spheres of influence within the empire. The empire, once a multi-ethnic power stretching across Europe, was now increasingly defined as a Muslim-majority state. In this fragile condition, Ottoman leaders sought not only foreign alliances but also an ideological foundation for renewal. It was in this context that Germany emerged as a new and promising partner.

Unlike Britain, France, and Russia, each of which had long-established imperial interests in Ottoman lands, Germany had no direct colonial claims in the Middle East. This crucial distinction made it an attractive ally. Germany’s growing economic power, industrial capabilities, and military expertise also appealed to the Ottoman leadership, which was searching for ways to modernize and strengthen the empire against its traditional European rivals. Moreover, Ottoman leaders recognized that colonial rivalry between Britain, France, and Russia provided an opening, as by aligning with Germany, the only major European power without Muslim colonies, the empire could hope to exploit divisions among its adversaries and even appeal to Muslims living under colonial rule.

One of the pivotal moments that marked the beginning of deeper Ottoman-German relations was the rise of Kaiser Wilhelm II to the German throne in 1888. Unlike his predecessor Otto von Bismarck, who had been cautious about Middle Eastern entanglements, Wilhelm II pursued an ambitious foreign policy known as Weltpolitik. This expansionist strategy aimed to increase German global influence, particularly by forging closer ties with the Ottoman Empire as a counterbalance against Britain and France.

Sultan Abdulhamid II, who ruled from 1876 to 1909, saw Germany as a useful counterweight to British and French interference. His mistrust of these powers was deeply rooted: Britain had occupied Egypt in 1882, France had tightened control over North Africa, and Russia continued to threaten Ottoman territories in the Caucasus and Balkans. Facing these challenges, Abdulhamid turned increasingly toward Pan-Islamism, positioning the sultan–caliph as the spiritual leader of Muslims worldwide. This was not merely domestic policy but also an instrument of international diplomacy. Abdulhamid cultivated the slogan: “The Ottoman State is the only true Islamic state, and the Sultan is the caliph,” presenting the empire as the natural protector of Muslims under European rule. While modernist Islamists in other parts of the Muslim world sought reform through liberal or interpretive readings of Islamic law, Abdulhamid’s state-sponsored Pan-Islamism was more conservative, cautious in tone, and explicitly defensive against Western imperial encroachment, comparable in spirit to Russian Pan-Slavism or German Pan-Germanism.

Germany proved an ideal partner for this strategy. By appearing sympathetic to Islamic sentiment and free of colonial entanglements in Muslim-majority lands, Germany could present itself as a “friend of Islam.” Wilhelm II’s state visits to the Ottoman Empire symbolized this partnership. His first visit in 1889 helped establish a personal bond with the Sultan. His second visit in 1898, orchestrated with great fanfare, was even more significant. Traveling to Istanbul, Jerusalem, and Damascus, the Kaiser delivered speeches presenting himself as a protector of Muslims. His declaration at Saladin’s tomb in Damascus was received warmly in Ottoman circles, even if it was primarily intended to undermine British and French colonial authority. For Abdulhamid, however, the propaganda value was real: the Ottoman caliphate could now claim support from a major European monarch.

This ideological convergence also had concrete political functions. Abdulhamid sought to harness Pan-Islamism as a unifying ideology after the trauma of territorial losses, demographic upheavals, and the disillusionment of constitutional politics, the Ottoman parliament had been dissolved after the 1877–1878 war. The empire, crowded with refugees from the Balkans, needed a new form of legitimacy. Instead of constitutionalism or liberal reform, Abdulhamid reintroduced an authoritarian model of governance reminiscent of Prussian-style state centralization, with Pan-Islamism as its ideological pillar. In this framework, Germany’s role was not only technical or military but also ideological, as German officials encouraged Ottoman Pan-Islamic outreach in India, North Africa, and Central Asia.

At the same time, Abdulhamid remained pragmatic. While he projected an image of an omnipotent caliph, bearing titles such as zi’lullahi fi’l-arz (“shadow of God on earth”), he was careful to maintain moderation, avoiding rhetoric that might alienate either conservative Muslims or modernist reformers. In practice, Pan-Islamic initiatives had mixed results. For instance, Ottoman consuls in places like Java were expelled by colonial authorities for stirring unrest, while correspondence with Muslim leaders in Egypt and India often yielded more symbolic than practical outcomes. Even high-profile projects like the Hejaz Railway, financed partly by donations collected in the name of the caliphate, depended heavily on German capital and engineering.

German influence also became increasingly visible in the military. Abdulhamid welcomed German officers such as Colmar von der Goltz, whose service from 1883 to 1895 reshaped Ottoman military education and doctrine. This was more than a technical partnership; it was a political choice to entrust reform to Germans rather than to Britain or France. The Sultan’s trust in Germany was so strong that he even tolerated German ambitions that elsewhere might have aroused suspicion, such as attempts to establish footholds in Anatolia. His preference for Germany was reinforced by bitterness toward France, after its seizure of Tunisia, and by distaste for republicanism, which clashed with his monarchical worldview. In contrast, he considered Germans disciplined, industrious, and culturally compatible, with Turks sometimes described as the “Germans of the East.”

Although Abdulhamid was eventually deposed in 1909 and the Young Turks initially sought to diversify foreign ties, German influence did not wane. The Balkan Wars further discredited Britain and France in Ottoman eyes, while Germany seemed increasingly indispensable for both military modernization and ideological support. By the eve of the First World War, the Ottoman Empire’s political and ideological trajectory had positioned it firmly in Germany’s orbit. The alliance that followed in 1914 was not the product of sudden opportunism but the culmination of decades of converging interests: an empire seeking survival through Pan-Islamism and authoritarian centralization, and a rising power eager to project influence by presenting itself as the unlikely friend of Islam.

Economic Influence

By the late 19th century, Germany had emerged as a formidable industrial and economic power, seeking new markets, raw materials, and geopolitical partners beyond Europe. The Ottoman Empire, weakened by decades of territorial losses, administrative inefficiencies, and financial instability, presented a unique opportunity for Berlin. Prior to the 1880s, Germany’s commercial presence in Ottoman lands was limited and fragmented. Early ventures, such as the Deutscher Handelsverein, operated briefly but lacked the capital, infrastructure, and banking networks necessary for sustained engagement. While Austria-Hungary had established trade along the Danube and the German language persisted as a commercial lingua franca, organized German economic penetration into Ottoman markets only became significant in the 1880s. German commercial activity at this stage depended on well-capitalized banks, rail transport, and maritime logistics to establish a foothold.

The transformation of German economic influence coincided with broader geopolitical shifts following the Congress of Berlin, which left the Ottoman Empire isolated, territorially diminished, and in search of reliable allies. With the loss of Balkan territories, including Albania, northern Greece, and Macedonia, and the cession of Kars and Ardahan to Russia, the empire had become a multiethnic state with a Muslim majority, seeking to consolidate its internal authority while maintaining sovereignty against European powers. Germany offered an attractive alternative to Britain and France, who were increasingly perceived as protectors of Christian minorities and potential colonial threats. Germany positioned itself as a neutral yet technologically advanced partner, ready to invest in infrastructure, finance, and industrial development without direct territorial ambitions in the Middle East.

German trade treaties and infrastructure initiatives accelerated economic penetration. The 1880 trade arrangements under the Zollverein facilitated initial commercial exchange, but the 1890 German-Ottoman trade treaty significantly enhanced German advantages. This treaty increased the number of Ottoman goods eligible for customs reductions from 605 to 720 and created de facto preferential treatment for German merchants, who benefited from diplomatic backing, modern banking support, and efficient transport networks. In practice, while Ottoman merchants were nominally granted reciprocal privileges in Germany, the balance heavily favored German traders. German exports to the empire included machinery, electrical equipment, steel, chemicals, and military supplies, while Ottoman exports, particularly Anatolian-grown tobacco, cotton, and opium, found a growing market in Germany. German investment in industrial infrastructure also expanded, with Siemens providing telegraph and communication systems and AEG (Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft) pioneering electrification in Istanbul and other major cities.

Transport innovations were central to German commercial success. Railways and maritime routes reduced shipping costs, enabling German goods to penetrate markets that had previously been dominated by Britain and France. By the 1880s, German and Austrian-Hungarian commercial share of Ottoman foreign trade was 18 percent, rising dramatically to 42 percent by 1909, reflecting the growing dominance of Central European economic influence over traditional Western powers. Rail transport not only facilitated trade but was strategically vital: the development of the Berlin-Baghdad Railway, overseen by Deutsche Bank and constructed with German engineering expertise, connected Istanbul to central Anatolia and eventually Baghdad, with the ultimate goal of reaching Basra and the Persian Gulf. Estimated at 200 million gold marks, the railway facilitated the transport of wheat, cotton, and livestock, provided efficient troop mobility, and secured access to Mesopotamia’s burgeoning oil reserves, critical as Germany’s oil consumption increased tenfold between 1870 and 1906. The Izmit–Ankara segment, awarded in 1888, marked the beginning of large-scale German investment in Ottoman infrastructure, which extended beyond railways to port construction, bridges, tunnels, and urban development.

German financial penetration reinforced these commercial and infrastructural gains. Deutsche Bank played a pivotal role in funding railways, industrial projects, and modernizing Ottoman banking practices. By 1914, German banks held approximately 25 percent of Ottoman external debt, compared to 40 percent held by French creditors and 20 percent by British lenders. German financial engagement often coupled loans with technical assistance, ensuring that investments supported industrial modernization as well as fiscal control. The Ottoman Public Debt Administration, dominated by European creditors, saw German influence grow alongside these loans, providing leverage over Ottoman economic policy. The Ottoman government’s caution in new borrowing, particularly during Abdulhamid II’s reign, directed foreign capital toward infrastructure and banking rather than mere debt financing, creating opportunities for German banks and investors to gain prominence without overwhelming the empire’s finances. By the 1890s, foreign investment in the Ottoman Empire concentrated on railways (41 percent) and banking (23.5 percent), while industrial investment accounted for only 10 percent. German firms also invested selectively in mining, though their industrial reach remained more limited compared to French and British enterprises. Nevertheless, German contributions to the Ottoman treasury and infrastructure were often more immediately beneficial than those of France, particularly in the period between 1888 and 1896.

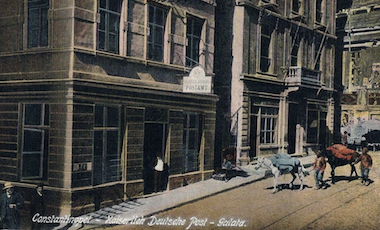

Urban modernization and cultural engagement accompanied Germany’s economic expansion. German engineers, architects, and planners were integral to projects in Istanbul, Izmir, and Beirut, constructing roads, bridges, water supply networks, and port facilities, including the Haydarpaşa terminal. German technical institutes, schools, and hospitals provided education and professional training for Ottoman bureaucrats, engineers, and technicians, cultivating a domestic workforce skilled in German methods and fostering a perception of Germany as a cooperative and technologically advanced partner. At the same time, German commercial and cultural presence reinforced broader geopolitical strategies. By supporting infrastructure and technical modernization, Germany facilitated Ottoman administrative reform and military modernization, consolidating the empire’s control over Anatolia and Mesopotamia while indirectly securing German access to strategic resources and markets.

Germany’s economic penetration was inseparable from strategic and resource considerations. As Ottoman influence in Asia waned, Germany emerged as the only major power willing and able to support the integrity of the empire’s Asian territories, including the resource-rich regions of Mesopotamia. German industrial and military needs, particularly for oil and other raw materials, were increasingly dependent on access to Ottoman lands, and German rail and shipping investments were instrumental in securing these supply lines. The Berlin-Baghdad Railway, along with other transport infrastructure, ensured that German access to oil, trade, and raw materials was protected while enhancing the empire’s ability to mobilize resources for internal development and defense.

Despite the successes of German economic expansion, significant limitations persisted. Ottoman dependence on German loans, industrial imports, and technical expertise reinforced patterns of economic vulnerability. Strategic projects such as the Berlin-Baghdad Railway served German interests, including securing trade routes and access to raw materials, as much as Ottoman development goals. The outbreak of the First World War highlighted the fragility of this economic relationship: the Entente naval blockade disrupted trade, overstretched Ottoman resources, and exposed the dangers of over-reliance on German financial and technical support.

By 1914, Germany had become the Ottoman Empire’s second-most important economic partner, surpassed only by France in total investment, yet increasingly central to fiscal policy, industrial modernization, and infrastructure. German trade, finance, engineering, and cultural institutions had left a profound imprint on Ottoman society, shaping urban development, military modernization, and administrative efficiency. German engagement accelerated modernization, integrated new technologies, and strengthened the empire’s capacity to manage internal and external challenges, but it also entrenched patterns of foreign dependency and strategic vulnerability.

Military Missions and Strategic Influence

German military missions in the Ottoman Empire during the late 19th and early 20th centuries constituted a pivotal dimension of Ottoman-German relations, encompassing military modernization, political influence, and strategic alignment. The Ottoman army, once formidable, had long struggled to reconcile traditional military practices with modern European models. Until the aftermath of the Congress of Berlin, Ottoman forces operated in a hybrid system, incorporating elements of British, French, and Prussian military practices alongside entrenched Ottoman traditions. The political and military panic generated by the Congress of Berlin, combined with the empire’s internal instability and external threats, created conditions that made Germany’s intervention both desirable and strategically opportune. Germany, newly unified and possessing a modernized, highly respected army, presented an ideal partner capable of supplying both expertise and technology. The Ottomans’ turn to Germany was not merely pragmatic; it reflected a shared interest in countering British and Russian influence, as well as Germany’s broader ambitions to extend its strategic footprint beyond Europe.

The arrival of Colmar von der Goltz in 1883 marked a turning point in Ottoman military reform. His mission, lasting until 1895, sought to professionalize the Ottoman army across organization, training, and operational capabilities. Unlike previous foreign advisors, German officers like von der Goltz were integrated into the Ottoman military under unique contractual arrangements: soldiers and civilian experts entering Ottoman service were governed by German military or civil law, not Ottoman regulations, and were largely insulated from local disciplinary authority. This arrangement generated both operational autonomy and diplomatic debate, drawing attention in Berlin and even in the British House of Commons. Von der Goltz’s reforms were comprehensive, introducing modern European tactics, rigorous officer training, and systematic operational planning. He also prioritized artillery modernization and fortification upgrades, often directing large orders to German manufacturers such as Krupp. The modernization extended beyond equipment; von der Goltz emphasized embedding German strategic thinking and organizational principles, thereby gradually aligning the Ottoman army with the German general staff system.

While von der Goltz’s contributions were significant, their implementation faced multiple obstacles. Ottoman commanders and the sultan himself, although publicly supportive of reforms, were often reluctant to adopt measures that might destabilize existing power structures or strain the empire’s limited financial resources. Reports prepared by German advisors frequently outlined reforms that were technically sound but financially burdensome, highlighting the structural limitations of the Ottoman state. Cultural differences and resistance among Ottoman officers further complicated reform efforts. German officers were accustomed to hierarchical discipline and efficient command structures, while Ottoman officers operated under a system shaped by tradition, patronage, and political considerations. As a result, many German officers initially struggled to command effectively or gain the respect of Ottoman counterparts. Over time, recognizing the limits of direct reform, officers increasingly focused on documenting the army’s condition and reporting to Berlin, while leveraging modest successes to secure their positions and influence.

Von der Goltz’s unique effectiveness among German advisors stemmed from his ability to navigate these constraints. Unlike many colleagues, he was able to exert influence over Ottoman commanders, ensuring that reform proposals translated into tangible outcomes, especially in terms of armaments and fortifications. His recommendations for strengthening defensive positions along the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles, and procuring modern artillery, frequently resulted in substantial orders for German manufacturers. Even when initiatives appeared unsuccessful or were initially ignored, von der Goltz ensured that the modernization of the Ottoman army proceeded in a manner closely aligned with German strategic interests. His career exemplified a broader pattern among ambitious German officers: the pursuit of professional advancement and prestige in the Ottoman context, combined with the opportunity to apply German military expertise in a high-impact environment. For officers, rapid promotion in the Ottoman army, coupled with equivalent or higher rank recognition in Germany, made service in Istanbul professionally and personally attractive. Many German advisors were motivated not only by reformist ideals but also by the financial and social incentives offered, including salaries, medals, and honors that often exceeded what Ottoman officers received.

The broader German presence in the empire intensified under Kaiser Wilhelm II, whose aggressive Weltpolitik aimed to extend Germany’s influence beyond Europe. Wilhelm’s 1898 visit to Constantinople symbolized the deepening Ottoman-German partnership and reinforced the alignment of military, political, and economic objectives. By the late 1880s, the Ottoman army was increasingly dependent on German expertise, weapons, and logistics, gradually merging with German organizational norms. The empire’s reliance on German advisors extended across the military hierarchy, from strategic planning to the education of officers, and facilitated Germany’s broader industrial penetration into Ottoman arms production and infrastructure.

The arrival of General Otto Liman von Sanders in 1913 marked another pivotal phase. Tasked with overseeing military reforms and commanding during a period of rising Balkan tensions, Liman von Sanders worked closely with Enver Pasha, the newly appointed Minister of War and a fervent advocate of modernization. Enver viewed the German partnership as essential for the survival and resurgence of the Ottoman Empire. Unlike some of his predecessors, Enver actively sought to integrate German strategies and technologies into Ottoman operations, creating a dynamic partnership that would shape the Ottoman war effort in the First World War. Yet this collaboration was marked by tension. Enver’s assertive personality, authoritarian approach, and nationalist ambitions sometimes clashed with the disciplined, methodical approach of German officers, illustrating the broader difficulties of transplanting foreign military expertise into an institution with deeply rooted traditions and political sensitivities.

German advisors were also instrumental in improving operational planning and discipline, particularly during the defense of Gallipoli in 1915. Their guidance on fortifications, troop deployment, and resource management enabled the Ottomans to mount a successful defense against a numerically superior Allied force. Nonetheless, systemic weaknesses, including logistical challenges, uneven command efficiency, and overextension, limited the long-term effectiveness of German-led reforms. While German involvement strengthened the Ottoman military’s capabilities and strategic awareness, it could not compensate for the empire’s deeper structural vulnerabilities or resolve the complex political and economic pressures that ultimately contributed to its collapse.

The German mission’s success was thus a combination of technical expertise, strategic foresight, and personal ambition, tempered by political and structural constraints. Von der Goltz exemplified the ideal reformer: knowledgeable, ambitious, and able to navigate Ottoman politics while ensuring that modernization produced tangible outcomes. The broader cadre of German officers, motivated by advancement, financial incentives, and professional prestige, contributed to embedding German systems and doctrine within the Ottoman army, even as cultural differences, internal resistance, and resource limitations moderated the impact of their reforms. These missions also facilitated Germany’s economic penetration, as Ottoman reliance on German arms and technology ensured a consistent market for German industry.

Ultimately, German military missions left a lasting imprint on the Ottoman army, producing a force more professional, disciplined, and strategically aware. They laid the foundation for the Ottoman-German alliance during the First World War and established mechanisms of cooperation that extended beyond the battlefield to encompass industrial, logistical, and political dimensions. Yet the limitations of this relationship, particularly the tensions between ambitious Ottoman leaders like Enver Pasha and German officers, alongside systemic financial and structural constraints, underscore the reality that even the most comprehensive foreign-guided modernization could not secure the empire’s long-term survival in the face of global conflict and internal decay. The German military mission in the Ottoman Empire thus stands as a testament to the potential and limits of military reform, where strategic ambition, personal initiative, and industrial interests intersected with the enduring complexities of Ottoman politics and society.

German Cultural Expansion

The cultural relations between the Ottoman Empire and the German Empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were a carefully orchestrated aspect of a broader strategy that sought to intertwine political, economic, and military interests with cultural influence. Germany’s cultural expansion into the Ottoman Empire was multifaceted, encompassing diplomacy, education, media, archaeology, and the arts, yet it was not the transplantation of the full richness of German culture. Instead, it was a selective, surface-level introduction of German ideas and prestige, largely tailored to serve Germany’s political and economic goals in the region rather than genuinely enrich Ottoman intellectual life. While German schools, societies, and institutions spread in key Ottoman cities, these efforts focused more on shaping a favorable environment for German trade, political influence, and strategic interests than on transmitting the depth of German philosophy, literature, or sciences, which were largely absent from the curriculum; instead, the Ottoman elite encountered a curated, instrumentalized version of German culture, often mediated through French translations and adapted for local consumption.

The German educational presence, while limited in scale compared to the extensive French, British, and American schools, was a key instrument of cultural expansion. By 1898, German-language schools existed in Istanbul, Izmir, Beirut, Haifa, and Salonica, educating only a few hundred students, yet these institutions were designed to cultivate an Ottoman elite sympathetic to German interests. They were intended not for religious propaganda but to advance Germany’s political, economic, and strategic influence. German experts advocated for additional schools in critical Ottoman regions, particularly along the Baghdad Railway corridor, reflecting Germany’s strategic ambitions and the need for trained local personnel to support German enterprises. Despite these ambitions, German cultural penetration faced challenges. Local populations often preferred British, French, or American schools, and initiatives such as the German schools in Palestine struggled when competing with Jewish colonizers or other educational models. Nevertheless, in the early decades of the 20th century, German schools, orphanages, and similar institutions spread, particularly along strategic transportation corridors, supporting the infrastructure of German influence.

Archaeology became another critical avenue for cultural influence. German Orientalists and scholars rapidly organized research activities in the late 19th century, combining academic pursuits with a strategic appropriation of the Ottoman Empire’s material heritage. The looting of sites such as the Pergamon Altar, often justified as scientific exploration, reflected both a disregard for local expertise and a deliberate effort to assert Germany’s intellectual and cultural presence. These excavations, conducted by associations such as the Vorderasiatische Gesellschaft, the Münchener Orientalische Gesellschaft, the Deutsche Verein für Erforschung Palästinas, and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für die Erforschung Anatoliens, combined archaeological activity with political aims. By integrating scholars and political experts under the Deutsche Vorderasien Komitee after 1908, Germany sought to ensure that archaeological and cultural work directly supported its strategic goals, blending research, propaganda, and influence in one coordinated effort. These institutions also provided a platform for German experts to cultivate ties with Ottoman administrators, engineers, and intellectuals, strengthening the perception of Germany as a modernizing force in the Middle East.

The press and media played a complementary role in this cultural projection. German newspapers circulated in major Ottoman cities, while local publications highlighted German scientific, technological, and artistic achievements, framing Germany as a progressive and efficient model in contrast to the faltering influence of Britain and France. German achievements in military, educational, and infrastructural modernization were widely publicized, further reinforcing Germany’s image as a partner capable of assisting the Ottoman Empire in preserving sovereignty and pursuing modernization.

Germany’s influence was also visible in the urban and architectural landscape. High-profile gifts such as the German Fountain in Istanbul, built in a neo-Byzantine style with German baroque elements, symbolized Germany’s intertwined cultural and political presence. German architects and engineers contributed to the design of railway stations, public buildings, and, most notably, the Berlin-Baghdad Railway. This railway project was both an economic and cultural vector, facilitating trade and transport while cementing Germany’s role in shaping Ottoman infrastructure and urban planning.

Germany’s cultural mission in the Ottoman Empire functioned less as a genuine dissemination of intellectual traditions than as a carefully engineered projection of authority, designed to serve strategic goals. While it never achieved the broad cultural penetration of France, Britain, or the United States, it cultivated networks of elites through educational institutions, research societies, media outlets, and urban projects, making Ottoman engagement with German culture selective and oriented toward practical gains in technology, administration, military, and trade. By the outbreak of the First World War, this influence, though often superficial and constrained by local preferences and rival powers, had nonetheless reinforced political, military, and economic collaboration, creating a lasting foundation for the German-Ottoman alliance and leaving a legacy of selective cultural transmission, strategic education, and political alignment.

In sum, the German presence in the Ottoman Empire during the late 19th and early 20th centuries was far more than a series of isolated economic, military, or cultural initiatives; it was a comprehensive, multifaceted strategy that intertwined political influence, economic penetration, military modernization, and selective cultural projection. Germany positioned itself as a partner distinct from Britain, France, and Russia, offering technological expertise, financial support, and ideological alignment without the burdens of direct colonial ambitions. Through military missions, infrastructural projects, trade networks, and educational institutions, Germany not only modernized Ottoman capabilities but also cultivated a receptive elite that reinforced its strategic objectives. Yet this influence was inherently selective and instrumental: German culture was transmitted in a curated form designed to advance political and economic goals rather than to foster deep intellectual integration. By the eve of the First World War, these converging efforts had created a durable framework of interdependence, shaping the Ottoman Empire’s political, economic, and military trajectory while cementing Germany’s role as an indispensable ally. The legacy of this engagement illustrates the complex dynamics of power projection, where modernization, ideology, and strategic self-interest intersect, leaving a nuanced imprint on the empire that extended far beyond formal alliances or treaties.

![]()

PAGE LAST UPDATED ON 28 AUGUST 2025