On the Balkan front, relative quiet prevailed until November 1915, when Field Marshal Mackensen launched a coordinated offensive that unified German, Austrian, and Bulgarian forces in a concerted invasion of Serbia. The strategic rationale underlying this campaign was unambiguous: Serbia represented a critical obstruction along the route connecting Germany and the Ottoman Empire. General Putnik and his embattled Serbian forces, constrained by severe shortages of ammunition and supplies, found themselves increasingly vulnerable to the sustained and systematic advance of the Central Powers.

On the Balkan front, relative quiet prevailed until November 1915, when Field Marshal Mackensen launched a coordinated offensive that unified German, Austrian, and Bulgarian forces in a concerted invasion of Serbia. The strategic rationale underlying this campaign was unambiguous: Serbia represented a critical obstruction along the route connecting Germany and the Ottoman Empire. General Putnik and his embattled Serbian forces, constrained by severe shortages of ammunition and supplies, found themselves increasingly vulnerable to the sustained and systematic advance of the Central Powers.

On 3 October 1915, the Anglo-French Expeditionary Force, consisting of two divisions, disembarked at Salonica with the objective of reinforcing Serbian resistance. Salonica, located within neutral Greek territory, became the stage for this intervention. However, the Greek government, confined to issuing formal protests, refrained from taking any substantive action. The Allied powers aspired to provide refuge for the retreating Serbian army in Salonica, yet these plans were ultimately frustrated by the intervention of Bulgarian forces.

With their overland access to Salonica obstructed, the Serbian troops, confronted with increasingly desperate conditions, were compelled to undertake a perilous evacuation from Albanian ports. They subsequently reached safety through maritime transport to Greek territory. By the summer of 1916, the Allied presence in Salonica, commanded by French General Sarrail, had expanded to approximately 350,000 troops. This growing force posed a significant strategic threat to the Central Powers’ position in the Balkans, particularly to the critical railway network linking Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire.

On 26 May 1916, Bulgarian forces crossed the Greek frontier, advancing with marked determination. By August, their progress had carried them to the banks of the Struma River, closely pursuing the retreating Greek IV Army Corps. As the Balkan terrain reverberated with the movements of troops and the maneuvers of military formations, the Allied forces, undeterred by the evolving circumstances, seized the strategic initiative and directed their efforts toward the capture of Monastir.

Amidst these shifting dynamics of warfare, on 12 September 1916, the German High Command, overseeing the coordination of military operations, appealed to Enver Pasha for reinforcement on the Balkan front. Responding to this request on the very same day, Enver Pasha agreed to dispatch additional troops, a decision that added yet another significant episode to the unfolding narrative of the conflict.

Immediate Entrainment

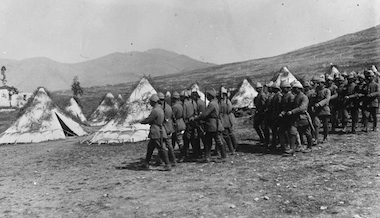

The 50th Infantry Division, stationed in İzmit to the west of Istanbul, received urgent orders for deployment. Acting swiftly, the troops advanced to Üsküdar on the Asian shore, crossing the Bosphorus by ferry and establishing encampments in Bakırköy. On 21 September, the division began its march toward the Balkans, with daily train departures culminating four days later as the final contingents arrived in Drama, Greece, and subsequently at the Bulgarian front near Salonica.

Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Şükrü Naili Bey, the 50th Division, upon reaching its assigned operational zone, integrated with the Bulgarian 10th Division. Their defensive sector extended from the mouth of the Struma River on the Aegean coast, encompassing the area between Lake Tahinos and Leftera Bay. The 158th and 169th Regiments were deployed in the forward positions, while the 157th Regiment was held in reserve. In view of the substantial British naval presence in the Aegean Sea, one battalion was strategically positioned to secure the division’s coastal flank.

As dusk descended on 31 October, a formidable Allied offensive commenced with considerable intensity. British forces, advancing from the flanks of Lake Tahinos, launched a determined assault against the 169th Regiment positioned to the south. By nightfall, their persistent attacks had brought them perilously close to breaching the initial defensive line. In a resolute act of defense, the Turkish unit successfully repelled the assault, though at a significant cost, 19 soldiers were killed, and total casualties reached 113 within the span of a single day.

Undeterred by earlier setbacks, subsequent Allied operations were soon undertaken. A combined force composed of French, Serbian, and Russian troops initiated a determined advance across Western Macedonia, encountering staunch resistance from a well-entrenched Bulgarian contingent defending the region’s rugged terrain. General Sarrail, the principal architect of this campaign, pursued a clear strategic objective: the capture of Monastir. His operational design culminated successfully on 19 November, marking a notable achievement within the broader context of the Balkan theatre of war.

One More Division

Amid the ongoing Romanian campaign, renewed demands for reinforcements emerged. Responding to a German request, Enver Pasha ordered the deployment of the 46th Infantry Division to Macedonia. This division was assigned to join forces with the 50th Division and the 16th Depot Regiment, together forming the newly established XX Army Corps. Command of this corps was entrusted to General Abdülkerim Pasha, who was designated to lead operations against British forces. Concurrently, the 177th Infantry Regiment was expanded and reorganized into the Rumeli Field Detachment, which was dispatched to Western Macedonia to cooperate with Bulgarian forces engaged in combat with the French along the Monastir front.

Amid the ongoing Romanian campaign, renewed demands for reinforcements emerged. Responding to a German request, Enver Pasha ordered the deployment of the 46th Infantry Division to Macedonia. This division was assigned to join forces with the 50th Division and the 16th Depot Regiment, together forming the newly established XX Army Corps. Command of this corps was entrusted to General Abdülkerim Pasha, who was designated to lead operations against British forces. Concurrently, the 177th Infantry Regiment was expanded and reorganized into the Rumeli Field Detachment, which was dispatched to Western Macedonia to cooperate with Bulgarian forces engaged in combat with the French along the Monastir front.

Upon arrival in Drama on 6 December, the headquarters of the XX Army Corps promptly established operational coordination with the 50th Division and their Bulgarian counterparts in the Second Army. The 46th Division was assigned responsibility for the defense of the Serez region, located to the north of Lake Tahinos, thereby relieving the Bulgarian 7th Division. The division faced a formidable task, as its defensive sector extended across a 30-kilometer front. To reinforce this critical stretch, Bulgarian artillery units and a cavalry detachment were strategically integrated into the defensive structure. Thus, preparations were completed for the next phase of operations in the Macedonian theater of war.

During the winter of 1917, Macedonia experienced an atypical calm, with the front remaining largely inactive. The XX Army Corps benefited from a period of relative respite, and for approximately three months, military engagements were limited to sporadic skirmishes at the regimental level. Meanwhile, across other theatres of war, the Ottoman Army was under considerable strain: Eastern Anatolia remained under Russian occupation, British forces continued their advance toward Jerusalem, and an elite corps of 29,000 soldiers remained stationed idly in Macedonia.

In an effort to reclaim these troops, Enver Pasha persistently appealed to the German High Command for their repatriation. Ultimately, on 10 March 1917, an agreement was secured, though it permitted the return of only a single division. The withdrawal of the 46th Division began in Drama on 19 March and was completed by mid-April. The episode of the Turkish 46th Division’s service in the Balkans thus amounted to little more than a brief European interlude. Upon its arrival in Istanbul, the division was promptly redeployed to the Mesopotamian front.

During April and May 1917, relative calm prevailed along the banks of the Struma River. In contrast, significant developments were unfolding in Mesopotamia, where British forces advanced and successfully captured Baghdad. Confronted with this escalating threat, Enver Pasha acted with urgency to organize the Seventh Army, a formation deemed essential for the defense of Baghdad. The situation necessitated the immediate redeployment of units stationed in Europe. Following negotiations with the German High Command, orders were issued to transfer the 50th Division from Macedonia to Aleppo. With the departure of this division, the only remaining Turkish military presence in the Balkan theatre consisted of the Rumeli Field Detachment, specifically the reinforced 177th Infantry Regiment, which continued to hold its position for an additional year.

Rumeli Field Detachment

On 29 December 1916, the Rumeli Field Detachment embarked on trains bound for Macedonia, ultimately arriving in the town of Köprülü, located just south of Skopje. This town carried considerable historical resonance, as it was here, in 1908, that a young Major Enver had boldly declared the restoration of constitutional rule, challenging the authority of the Sultan. In Köprülü, a number of volunteers joined the ranks, expanding the strength of the detachment to approximately 4,300 soldiers.

Amid the ongoing hostilities between the French, who had seized control of Monastir, and the Central Powers, the Turkish unit was ordered to take up positions approximately 15 kilometers north of the city in anticipation of a French offensive. Contrary to German expectations, however, the French forces prepared to launch their attack not from the north but from the western shores of the lake near Monastir. The conditions were thus set for a decisive engagement.

On 13 March 1917, the French offensive commenced, cutting through a corridor approximately 10 kilometers wide and 16 kilometers long, situated between Lakes Ohrid and Prespa. This maneuver represented a critical turning point, as allowing the French forces to advance unchecked would have placed the Bulgarian 1st Army and the German 11th Army to the north in jeopardy. Immediate counteraction was therefore required. On the same day, the Turkish detachment received orders to mobilize toward the lake region and to coordinate operations with the Bulgarian 2nd Division.

The confrontation was inevitable. The French 76th Division, bolstered by a significant numerical advantage, engaged the Bulgarian forces. Even with the arrival of Turkish reinforcements, the disparity remained stark; 15 French battalions faced only six battalions from the Central Powers in defensive positions. As the Rumeli Field Detachment reached Hotoshevo, located west of Lake Prespa, the French forces pressed forward relentlessly, pursuing the German and Austrian battalions that had been severely weakened by earlier engagements.

The course of battle shifted abruptly. A determined Turkish counterattack, reinforced by concentrated machine-gun fire from both Turkish and German positions, sowed confusion and disorder within the French ranks. A day of intense and unremitting combat ensued, culminating in a stalemate: the French advance was successfully halted, though the engagement inflicted heavy casualties on both sides.

With the French offensive blunted, the initiative now passed to the Central Powers. The Bulgarian command formulated a counteroffensive plan, notably without consulting Major Nazım Bey, the commander of the Rumeli Field Detachment. The strategy aimed to drive the French forces further south through the corridor, with the objective of securing the strategically significant Gorica–Trapezica line. The principal burden of this attack fell upon the Turkish detachment, while the participation of other units was conditioned upon the success of this initial assault.

At 2:00 p.m. on 1 April 1917, the Central Powers initiated a coordinated assault, preceded by a sustained artillery bombardment. As evening fell, Turkish infantry confronted well-fortified French positions, advancing resolutely with bayonet charges. Despite their determined efforts, the units suffered substantial casualties, compelling Major Nazım Bey to order a halt and consolidation of the battalions’ positions. At dawn on the following day, the French launched a vigorous counteroffensive, combining intense artillery fire with a determined infantry advance, which compelled the Turkish forces to withdraw to their original defensive lines.

The initial days of April 1917 witnessed significant Turkish losses, with 712 soldiers killed in action. The subsequent weeks were characterized by relative inactivity, as severe weather conditions, including heavy snow, imposed substantial logistical challenges on both sides. Nevertheless, the Turkish troops derived some comfort from the protection afforded by their durable German-made uniforms.

The severe cold was not the only source of hardship confronting the Turkish forces. Having suffered the loss of nearly one-third of their effective strength within the first eighteen days of engagement, they were starkly contrasted with their German, Austrian, and Bulgarian counterparts, who were stationed in less active sectors and periodically afforded periods of respite following intense combat operations.

Confronted with the escalating pressures of trench warfare imposed by the French, Major Nazım Bey sought support from the Bulgarian 22nd Division and Colonel von Thierry, the German regional commander. His repeated communications, requesting relief for his detachment and a period of respite, went unanswered, generating growing concern. In a state of increasing desperation, he escalated the matter to the commander of the German 62nd Corps; yet, his appeals continued to elicit silence.

Colonel von Thierry, frustrated by Nazım Bey’s persistence, lodged a formal complaint against the major with Enver Pasha. In response to the emerging conflict, Enver requested a comprehensive report from Major Nazım Bey. The report revealed apparent inconsistencies in the Germans’ approach to operational demands. Seeking redress, Enver appealed to the German High Command for the repatriation of the Rumeli Field Detachment to Turkey; regrettably, this request was ignored.

Feeling increasingly marginalized, Major Nazım Bey, despite his unwavering efforts, faced worsening conditions. Even basic necessities, such as obtaining potable water, became formidable challenges for the Turkish soldiers. While Enver Pasha regarded Nazım Bey’s concerns with skepticism, the major’s resignation on 10 July conveyed the seriousness of the situation. His departure marked the end of an era, with Lieutenant Colonel Ali Bey assuming command on 28 July.

In August, following a period of minor skirmishes, Lieutenant Colonel Ali Bey petitioned the German 62nd Corps command for a respite. His request was denied; instead, he was assigned the demanding task of leading a night assault to seize a strategic hill along the front line. On 5 September, this operation was successfully executed, though it resulted in the loss of 41 Turkish and two German soldiers.

for Ottoman victory

Undeterred, Lieutenant Colonel Ali Bey continued to report to Istanbul, as well as to the Bulgarian and German commands, regarding the increasingly adverse conditions faced by his troops. On 6 October, the Ottoman High Command issued orders instructing the Rumeli Field Detachment to prepare for repatriation to Turkey. However, the soldiers’ anticipation of relief was abruptly dashed. Merely two days later, Enver Pasha transmitted a contradictory directive: "Order for your return to Turkey is cancelled."

The rationale behind this sudden reversal remains obscure. The German High Command’s insistence on retaining the Turkish detachment suggests the presence of underlying political or strategic considerations. The months of October and November 1917 were characterized by relative operational inactivity, though the harsh winter conditions exacerbated the hardships endured by the Turkish forces. Throughout this period, Ali Bey maintained persistent correspondence with the German, Bulgarian, and Ottoman commands.

On 23 November, his sustained efforts were rewarded. A telegram from General Ludendorff, the second-ranking officer in the German High Command after Hindenburg, ordered the replacement of the Rumeli Field Detachment with a Bulgarian regiment, thereby facilitating their redeployment to another front.

Rest proved fleeting for the Rumeli Field Detachment, which remained stationed in Prilep until 11 February 1918. During this period, while engaged in routine training, the unit underwent a change in leadership as Lieutenant Colonel Ali Bey relinquished command to Lieutenant Colonel Sadık Bey. In February, the detachment returned to the lake region; however, the diminishing intensity of military operations foreshadowed the approaching end of hostilities.

By May 1918, the Rumeli Field Detachment received orders to withdraw to Turkey. At the end of June, the troops embarked from the Romanian port of Constanța, crossing to Batum on the eastern coast of the Black Sea. There, they were assigned to join the Third Army, thereby marking the conclusion of the Ottoman Empire’s military presence in the European theater of the First World War.

In retrospect, the deployment of the XX Army Corps to Macedonia can be regarded as largely unproductive. At a juncture when reinforcements were urgently needed on other fronts, approximately 25,000 troops remained largely inactive in the Balkans, a considerable strategic miscalculation and an unnecessary expenditure of manpower. In contrast, the Rumeli Field Detachment demonstrated operational effectiveness, achieving notable success and asserting control over French forces in the lake region surrounding Monastir.

![]()

PAGE LAST UPDATED ON 19 OCTOBER 2025